EDITOR’S SUMMARY: Sewer sludge has negative impacts on not only the environment, but human health as well. The reason shouldn’t surprise you, as it’s likely slapped you in the face before—man-made chemicals. Not easy to escape, right? The accumulation of biosolids, and waste treatment processes, produce a “sickening” situation. But there are proactive steps you can take, ways to speak up, and decisions on where to spend your money that can influence betterment for people, animals, and the Earth.

By Carter Trent

Americans have a poop problem: where to store the “stool.” Every time you go to the bathroom and flush the toilet, the waste seems to magically disappear. But it needs to go somewhere … How about putting it in your plants and food? That’s exactly what is happening today. Your feces travel to wastewater treatment plants where the excrement is processed, then packaged and sold as a product called biosolids, otherwise known as sewer sludge. The two terms are interchangeable; biosolids is most commonly used. This substance becomes an ingredient in compost, soil amendments, and fertilizer, sold to consumers, farmers, gardeners, and landscapers. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), which oversees the safety of sewer sludge, 31% of biosolids are used as fertilizer in agriculture. Another 25% are applied outside of agriculture, in areas such as home gardens, golf courses, and landscaping. The remainder is disposed of primarily in landfills, or by burning.

However unpleasant as it sounds, the reality is that your excrement has to be addressed, and there’s a lot of it to eliminate. Americans produce about 300 million pounds of poop daily, according to some estimates. Using your feces as fertilizer is one solution to deal with all that dung; it’s been the case for centuries. In Japan during the 1700s, people fought over who had the rights to human excrement. As an island, Japan’s access to resources at that time was limited, so human waste was an essential fertilizer for agriculture. Your poop is filled with nutrients that can benefit plants and crops. Your digestive system doesn’t consume all the nutrients available in the food you eat, taking just what it needs, and expelling the rest. The human body absorbs anywhere from 10 to 90 percent of the nutrients in food, depending on many factors. For example, the way a meal is prepared affects how well your body can take in the nutrients, referred to as bioavailability, with cooked foods generally being more bioavailable than raw. Age is another factor, since the older you get, the fewer nutrients your body absorbs. After all, a growing child needs more nutrients than an adult.

How All This Works

Biosolids are created using a series of steps, which can vary depending on the facilities and local regulations per city or state, but the general flow is as follows: A pretreatment process removes large debris that may get into storm drains or down toilets, including tree branches, diapers, and toys. Next, smaller particles, such as rocks, egg shells, and coffee grounds, are filtered out in the grit chamber. The remaining material is transferred to a settling tank where solid waste sinks to the bottom, and the liquids, called effluent, float to the top. The effluent is put through a secondary treatment and disinfection process before being released into waterways. As for the solid waste, microorganisms are introduced to reduce the level of pathogens, which are disease-causing microorganisms. This includes certain bacteria, viruses, and parasites. Minerals, such as lime or alum, may be added to reduce water content and odors. The remaining sludge is put into another tank where it’s subjected to more microorganisms. This step makes the sludge suitable for reuse by decomposing organic matter, which helps to further reduce pathogens, although they are not entirely eliminated. The remaining slurry is dried out and sold as biosolids. The idea of sewer sludge being used to fertilize your garden or the food you eat may not sound appealing. But according to Professor Sally Brown, a soil scientist at the University of Washington who has studied biosolids and wastewater treatment for years:

“This is a resource that’s really undervalued. If you do the carbon accounting, you see that biosolids actually capture carbon, unlike synthetic fertilizer, which is what farmers would otherwise be using.”

Professor Brown brings up a good point. Today, the majority of fertilizers are synthetic, comprising a $200 billion dollar market. For comparison, animal manure is a $4 billion dollar market, and like biosolids, can improve soil health, which is not possible from synthetic options. However, unlike biosolids, animal manure is not typically treated for pathogens unless it’s composted before land application. Biosolids make up an estimated $33 million of the fertilizer market. While there are benefits to biosolids, the problem with this muck is that it contains toxins. Some of these are the byproduct of your trip to the toilet. Pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs), including antibiotics, sunscreen, and body lotion, are not entirely absorbed when you use them, and the residuals end up in your waste. PPCPs are biologically active, meaning they are meant to have an impact on living organisms. Consequently, when they end up in the environment, they have an effect on humans and wildlife. The implications of this are not yet known, since research into PPCPs in the environment is still nascent. That said, studies have detected drugs, such as antidepressants, in the brains and livers of fish.

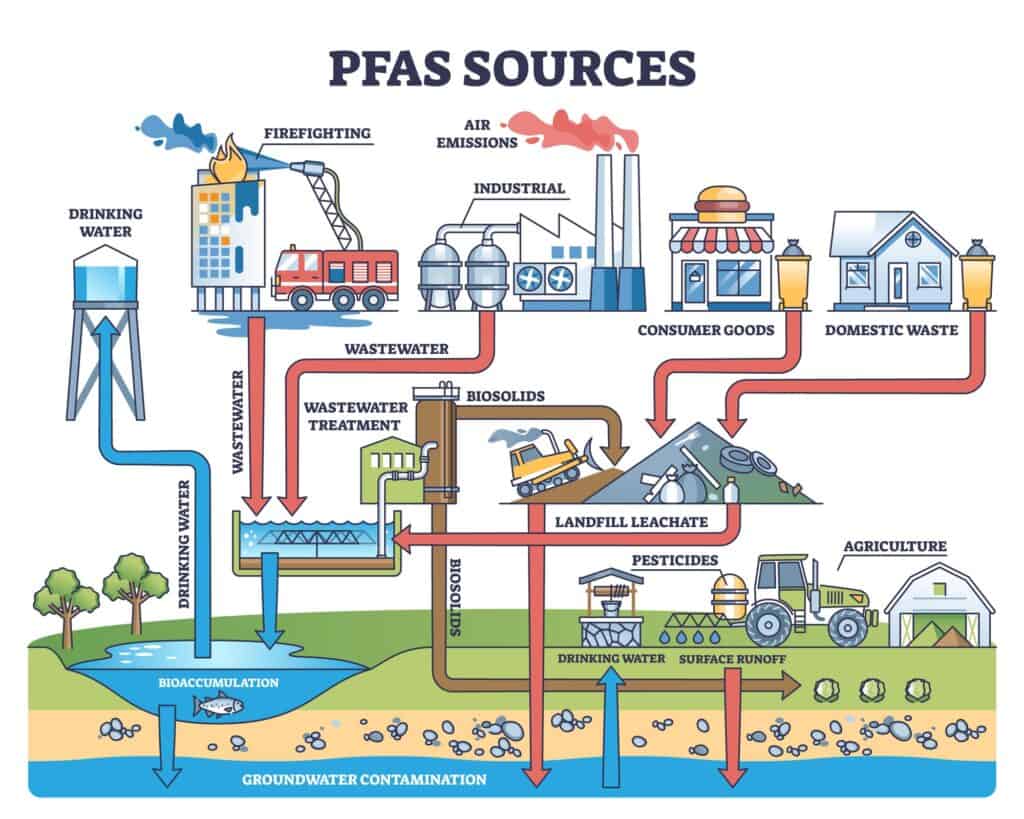

Adding to the toxic mess is the residue from soap, shampoo, and cosmetics that go down the drain when washed off; many of which contain harmful chemicals. If a neighbor uses pesticides in their garden, the next rain will wash those substances into storm drains. When you do the laundry, clothes made of polyester shed tiny plastic particles in the wash, not to mention the problematic surfactants in the detergents. All of these substances mix together at the wastewater treatment plant. That’s not all. Adding to this dangerous cocktail is the industrial runoff from businesses. For instance, the manufacturing facilities for pharmaceutical companies are a significant source of drugs in wastewater. According to research published in the journal Science of The Total Environment, these facilities discharge “pharmaceuticals at levels exceeding concentrations acutely toxic to aquatic organisms” into the sewage system. Although EPA regulations require pharma companies to pretreat waste from the manufacturing process before sending it to the wastewater plant, not all pharmaceutical compounds are entirely removed during this pretreatment step.

PFAS

Another example of pollutants in biosolids include per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). PFAS are called “forever chemicals” because they don’t break down. Once biosolids are applied to land, any PFAS chemicals contained in it remain in the environment, building up each time more sewer sludge is added. This also means PFAS accumulate in your body, where they can impact your health in many ways. Dr. Carmen Marsit, a professor and researcher at Emory University’s Rollins School of Public Health, said of PFAS:

“We see new data coming out of research that’s telling us that there are good, well-researched links between these types of chemicals and cancers, particularly kidney cancer and testicular cancer. And there is more research going on that could be linking it to other cancers. PFAS are also linked to various other endocrine-related type conditions, such as menstrual cycle alterations, infertility and thyroid disease… We’re concerned because they do have this ability to affect so many different types of organs, and they’re so prevalent in the environment and in people that we worry about their health effects.”

PFAS chemicals were invented in the 1940s, and are used in a variety of products, including cosmetics, waterproof clothing, dental floss, and nonstick pans. Manufacturers dump the chemical byproducts resulting from the manufacturing process into wastewater drains. A 2024 report by the Environmental Integrity Project confirmed that the EPA failed to regulate this kind of dumping. Consequently, PFAS end up in biosolids. Treatment plants are unable to filter out PFAS, pharmaceuticals, and other chemicals. According to Birguy Lamizana, an expert on wastewater and ecosystems for the United Nations, “Modern wastewater treatment plants mostly reduce solids and bacteria by oxidizing the water. They were not designed to deal with complex chemical compounds.” In fact, research published in 2023 showed the wastewater treatment process can actually increases the PFAS amount in biosolids, because as materials in wastewater break down, some release PFAS chemicals as a result. These toxins in biosolids are spread on pastures, then taken up by crops and grazed on by livestock, which end up in the meat and produce you eat.

PFAS and other toxins aren’t the only problems. After processing at the treatment plant, sewer sludge may still contain pathogens, depending on its biosolid classification. The EPA defines two classes: Class A and Class B biosolids. The Class A material is a higher quality, and must have all pathogens removed before being utilized on lands. Even so, Class A as well as Class B biosolids retain PFAS and other toxins that the treatment plant is not designed to eliminate. Class B, however, can contain disease-causing microorganisms, “which is why EPA’s site restrictions that allow time for pathogen degradation should be followed for harvesting crops and turf, for grazing of animals, and public contact,” according to the EPA. This means Class B biosolid fertilizer should be applied following EPA guidelines to allow natural processes, such as sunlight, to eliminate remaining pathogens. Nonetheless, following these guidelines is not currently mandatory. Class A biosolids are sold to all members of the public, including consumers, gardeners, and farmers. Class B is used in agriculture. But when Class B biosolids are spread by wind or water runoff to communities in the area, it results in people suffering from health issues, and drinking contaminated water.

A University Of Georgia study found that people living within a mile of land treated with Class B biosolids reported getting sick with burning eyes and lungs, skin rashes, or skin and respiratory tract infections. In 2018, the EPA’s Office of Inspector General released a report assessing how well the government was overseeing the safety of biosolids. This office is an independent organization within the EPA, responsible for conducting audits, evaluations, and investigations to ensure the agency operates in accordance with applicable laws and regulations. Its report stated:

“The EPA’s controls over the land application of sewage sludge (biosolids) were incomplete or had weaknesses and may not fully protect human health and the environment. The EPA consistently monitored biosolids for nine regulated pollutants. However, it lacked the data or risk assessment tools needed to make a determination on the safety of 352 pollutants found in biosolids. The EPA identified these pollutants in a variety of studies from 1989 through 2015. Our analysis determined that the 352 pollutants include 61 designated as acutely hazardous, hazardous, or priority pollutants in other programs.”

Could this biosolid poop problem be resolved by asking governments to ban the substance? That’s how Maine handled the issue. It was the first state in the U.S. to ban the use of biosolids on land in 2022 after discovering levels of PFAS so high, several farms were forced to shut down. One of those affected was Songbird Farms, which was purchased by farmers Johanna Davis and Adam Nordell in 2014. The previous owner applied biosolids on the soil, and later died of pancreatic cancer, which can be caused by PFAS chemicals. Testing at Songbird Farms in 2021 revealed the well water was contaminated by PFAS chemicals at levels over 400 times higher than Maine’s safety threshold of 20 parts per trillion. The crops and soil were also tainted by PFAS, forcing a recall of Songbird’s products, and the farm was closed down. Adam Nordell said, “This has flipped everything about our lives on its head.”

Ironically, legislation to prevent environmental damage is what led to the creation of biosolids. Wastewater was once dumped into oceans and rivers without any treatment. The levels of toxicity this created caused Ohio’s Cuyahoga River to catch fire in 1969, culminating in the Clean Water Act of 1972. As a result of this federal law, wastewater had to meet standards of cleanliness before it was allowed to be dumped into waterways. But that meant the resulting sewer sludge had to be dealt with somehow, hence the birth of biosolids. It’s easy to blame biosolids as the villain, but banning the substance means finding another way to deal with it. After all, no one will stop pooping for the foreseeable future. Putting it into landfills is a temporary solution since landfills don’t have infinite space, and toxins can seep into groundwater. Burning biosolids isn’t a strong solution either. The EPA noted “uncertainties remain” with using this approach because municipal waste combustors may send PFAS-containing emissions into the air. Rather than ban biosolids, the city of Tacoma, Washington, took a different approach. It championed standards for a class of biosolid of higher quality than Class A, resulting in the EPA’s use of a “class A exceptional quality” rating. This class exceeds the standards set for Class A. Tacoma adds a cooking process to the biosolid creation to ensure all pathogens are eliminated. That said, Tacoma’s sewer sludge, branded Targo, contains PFAS, but at concentrations below samples tested across North America.

Toward Positive Change

Researchers in Australia identified techniques for removing PFAS from biosolids using thermal treatments. For example, a process called pyrolysis uses high temperatures in the absence of oxygen. This heats the biosolid enough to break down PFAS chemicals, but since there’s no oxygen, the biosolid doesn’t catch fire, preserving the material. The challenge with this method is potential PFAS emissions. Choosing alternatives to biosolid fertilizer won’t spare you from PFAS. The U.S. Geological Survey found PFAS chemicals in nearly half the tap water in municipal water supplies across America. In fact, according to Dr. Marsit, everybody, from infants to the elderly, already have some level of PFAS in their bodies. However, tackling one problem at the source by eliminating toxins in biosolids could be a viable long-term remedy. Scientists are seeking solutions to do exactly that. The Water Research Foundation is evaluating different technologies in search of a way to sustainably address the contaminants in biosolids.

Another approach being investigated is vermiremediation. This is the use of earthworms to remove pathogens and toxins in soil. In the case of sewer sludge, research showed that earthworms were able to effectively clean the material “in cases where the sludge is not too contaminated with inorganic pollutants, especially heavy metals,” according to “Pilot-Scale Vermicomposting Of Dewatered Sewage Sludge From Medium-Sized Wwtp.” However, another study, “New insights into vermiremediation of sewage sludge: The effect of earthworms on micropollutants and vice versa,” confirmed vermiremediation had no effect on PFAS chemicals. An additional potential solution specifically to address PFAS toxins is the use of advanced oxidation processes (AOPs). This is a group of technologies using different methods, such as electricity and ultraviolet light, to break down PFAS chemicals in wastewater. AOP techniques show promise, but because PFAS encompass thousands of different types of chemicals, no one AOP approach has proven effective in eliminating all PFAS, while the high cost to implement AOPs is another challenge to adoption.

Stricter regulations, or an outright ban on toxic chemicals such as PFAS are also a means to keep these pollutants from getting to wastewater treatment plants in the first place. Governments are moving in the right direction. In 2024, the EPA passed the first federal regulations in history for PFAS pollution. But the new rules only cover six of the estimated 12,000 PFAS chemicals in use. States are taking up the cause as well. Colorado, Vermont, and Minnesota are among the states requiring monitoring for PFAS. Michigan has banned biosolids considered affected by industrial toxins. Other states, such as Arizona and Maryland, are collecting data to evaluate possible regulations. Kyla Bennett, science policy director for Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility (PEER), pointed out:

“It shouldn’t be this way, but right now, because the states and the federal government are acting so slowly, we have to take it upon ourselves to reduce our risk as best we can. So, education can go a long way in getting people to realize what they should and should not be buying, what they should and should not be using, what they should and should not be eating…It sucks that the government isn’t taking care of us. But people assume that if something’s legal, it’s safe. And that’s simply not true.”

You can take action by avoiding products containing toxins including PFAS. This is not easy since many goods you buy today are not properly labeled as containing PFAS, but it’s doable. Steer clear of nonstick cookware, and opt for stone, stainless steel, or cast iron. Look for cosmetics made from organic ingredients; research the products to make sure they don’t contain PFAS or other toxins, and make your own. For clothing and furniture, avoid those made of polyester, and seek out waterproof clothes that specifically state they are made without PFAS. The Green Science Policy Institute partnered with Northeastern University to produce a list of PFAS-free products. These include goods across a range of areas, such as apparel, shoes, furniture, and baby items. It can be a starting point to help you make informed purchase choices.

If you want to avoid biosolids in your food, buy organically-grown fruits and vegetables. The use of sewer sludge in organic food production is prohibited by law. For your plants or home garden, seek fertilizer or soil amendments made without biosolids, but even alternatives contain PFAS at varying levels. The best option is to either choose a product with the lowest PFAS level, or make your own fertilizer at home. As you can see, solving America’s poop problem isn’t simply a matter of avoiding biosolids. Fortunately, the growing awareness of the toxins in sewer sludge means scientists and governments are trying to find solutions. And by taking action through the product choices you make, you’re also cultivating a path forward to help remedy this situation.

~

Published on December 12, 2024.

If you’ve found value in this article, please share it!

To support the research and health education of AVFC editorial, please consider making a donation today. Thank you.