EDITOR’S SUMMARY: What’s truly “extreme”? For some, it’s colon cleansing, cold plunges, or the carnivore diet. For others, it’s the steady rise of overprescribed medications, invasive surgeries, and a diet dominated by ultra-processed food-like-products. It all comes down to perspective. A closer look at the long, global history of enemas—used medicinally for millennia—offers more than a history lesson; it might just reshape your take on what counts as real, effective medicine.

By Jennifer Wolff-Gillispie HWP, LC

As early as 1600 BC, the practice of cleansing the body, particularly the colon, has been a topic of interest across cultures. Whether it was for therapeutic, spiritual, or preventive health purposes, the use of enemas and colonics has persisted over centuries. These methods of internal cleansing, although controversial in some modern medicine circles, have their roots deeply embedded in both conventional wisdom and integrative healing theories. The history of enemas dates back to ancient Egypt, where it was believed that feces left in the colon would putrefy and cause disease. The Egyptians believed the body was filled with channels, much like irrigation canals. When those passages became blocked, waste backed up—and illness followed.

That belief led many Egyptians, especially among the upper and royal classes, to administer enemas as often as three times a month. This is documented in the writings of 5th century Greek historian Herodotus. Fashioned from hollowed out animal bone, or reeds with an attached gourd or animal bladder (to retain the desired healing liquid), these simple enemas, although rudimentary and perhaps uncomfortable, got the job done. The famous Egyptian papyri of Ebers, one of the oldest compendiums of medical writings dating back to 1550 BC, documents the use of enemas, primarily for gastrointestinal issues. While there is some doubt in academic circles as to the interpretation of papyri, it is widely accepted that it reads as follows:

“When thou examinest any person who is suffering in his abdomen and thou findest that he is ill in both sides, his body swollen when he takes nourishment, his stomach feels uncomfortable at its entrance, fight thou against it with soothing remedies. If it moves, thereafter under thy fingers give him an enema for four mornings.”

Another medical text, the Chester Beatty VI papyrus (1305–1085 BC), describes enemas being used to treat anal pain, prolapse, hemorrhoids, itching, and bladder issues. The mixture used in these applications combined three components: a “vehicle” (water, beer, or milk), an emollient (oil or honey), and a medicinal agent (hemp, herbs, and spices). It was advised that instead of using the enema to evacuate the bowels, the contents should be retained overnight and expelled the next day. This way the treatment could have an opportunity to work on the intended ailment and return the body to homeostasis. In the textbook, “History of Applied Science and Technology,” it is stated:

“Ancient Egyptians recognized health and illness as expressions of an individual’s relationship with the world… One’s good health meant that maat [order, balance, justice] was balanced, while illness, injuries, and other issues indicated that maat was not in order. Health depended on this balance…”

People of early Egypt believed that a clean body was necessary for actualized mind, body, and spiritual balance, a concept that would eventually spread to the Greeks and Romans. In this ancient civilization, the material and spiritual worlds were intimately linked, and for healing to occur, both needed to be considered. Because of this, enemas were often part of religious rituals and rites. Later, in old-world Greece, the practice became more refined. Hippocrates, often regarded as the “father of modern medicine,” was said to have prescribed enemas to treat varied digestive disorders. His texts, although vague on the exact methods, emphasized the importance of proper bowel function for overall health. He believed that the body should regularly move its excrement through the alimentary canal, and if that wasn’t happening, wellness could be restored through colon detoxification via enema:

“If the previous food which the patient has recently eaten should not have gone down, give an enema if the patient be strong and in the prime of life, but if he be weak, a suppository [a solid medication inserted into the rectum or vagina that melts or dissolves once inserted] should be administered, should the bowels be not well moved on their own accord.”

The Romans, known for their advanced infrastructure and sophisticated hygiene systems, also incorporated enemas into their medical regimen. Galen (130–210 AD), a prominent Roman physician, advocated for the use of enemas to restore balance in the four humors—blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile—which were believed to govern a person’s health and corresponded with the natural elements of earth, air, fire, and water. This was a firmly held belief of the time referred to as the “humoral theory of medicine,”a conjecture that persisted for almost 2000 years. It was eventually replaced by modern, empirical science based on the scientific method beginning in the 19th century. Galen’s teachings influenced medical practices for centuries, and his thoughts on enemas as both preventative and therapeutic became widely accepted.

The distinguished Arab physician, Avicenna (980–1036 AD), also promoted enemas saying they were “an excellent agent for getting rid of the superfluities [things unnecessary] in the intestinal tract.” Chang Chung-ching, often referred to as the “Chinese Hippocrates,” wrote about the use of enemas—specifically, pig’s bile—administered to patients with typhoid, caused by the Salmonella Typhi bacteria. Interestingly, modern research has shown bile to have antimicrobial properties. During the Renaissance of the 15th and 16th centuries, renewed interest in anatomy and physiology was fueled in part by artists like Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo, both of whom dissected human bodies to better understand their structure and function. As curiosity about the body’s intricacies expanded, so too did the methods of internal cleansing. Physicians began to use enemas not only for digestive issues, but also as a means of treating a variety of ailments—from headaches to fever. In the article, “Health and Wealth in the Renaissance,” author Stephen Mortlock discusses how the enema had its own “rebirth” during this time:

“Although the enema had been around for a long time, it gained more popularity in the Renaissance era. Once relegated to the duty of a skilled practitioner, it was during this time that the use of the enema (or clyster, as they were often referred to) began to be employed at home. The French monarch Louis XIV (1638–1715) was fond of this therapy and practised it daily. Taking cues from a similar Native American tradition, Western healers also made a habit of performing tobacco-smoke enemas for respiratory conditions, while they preferred liquid tobacco enemas for treating hernias. And on the subject of enemas, smoke was not the only thing being introduced to Renaissance rectums in the name of good health. As an effective method of getting medicine in the body and targeting intestinal issues, the enema was central to the era’s medical arsenal and was considered appropriate treatment for everything from constipation to cancer.”

The Cultural Embrace of Cleansing

By the 1850s, enemas became a common practice in Western medicine, particularly for constipation—one of the most common gastrointestinal disorders. During this time and into the 1920s, the awareness of colon cleansing expanded beyond the therapeutic realm and into popular culture. The health reform movement (1880–1920), which sought to improve public health, sanitation, and overall wellness, also led to the development of expensive resorts and spas catering to both the wealthy and the ill. The affluent would flock to these destinations to partake in therapies often financially out of reach for the common person. From mineral baths to enemas, these “water cures” became the fashionable way to address one’s health. It was during this period that colon hydrotherapy (aka colonics) began to take shape as a practice, reaching its peak in the early 20th century.

By this time America also saw the development of more formalized systems for colon cleansing, with practitioners like Dr. John Harvey Kellogg at the forefront. Kellogg, a prominent figure in health reform, advocated the use of enemas to remove toxins and impurities from the body. He said, “More people need washing out than any other remedy.” Kellogg’s methods, often rooted in his own interpretations of hygiene and the importance of digestive health, were in many ways a precursor to the holistic health movements of the 20th and 21st centuries. (Note: It was his brother Will who founded the well-known Kellogg cereal company—John had no part in that venture.)

One such early trailblazer in this movement, Dr. Max Gerson, remains an icon and valued source of health wisdom for people today. Gerson, a German physician living the 1920s believed in the concept of autointoxication, which became popular with his contemporaries. It was believed that this condition occurred when food was not processed quickly enough through the body, causing it to rot and systematically create illness. He adhered to a vegan diet and incorporated coffee and castor oil enemas into his healthcare regimen. In part, his motivation stemmed from previous struggles with migraines, a factor that contributed to the development of Gerson Therapy. After his death, his family founded the Gerson Institute in San Diego, CA, which continues to assist people with degenerative and chronic diseases, including cancer, and remains in operation today.

Despite these benefits, the long-term use of enemas is not without controversy. Gastroenterology of Greater Orlando warns that “while enemas can provide temporary relief, overuse can lead to dependency and disrupt the colon’s normal function.” This is a concern among healthcare providers who caution against using enemas regularly without medical supervision. Contemporary medicine largely views practices like enemas and colonics with skepticism, raising concerns about their effectiveness and safety. Among concerns are electrolyte imbalance, bowel perforation, infection, and as previously mentioned, dependency. Dr. Anuradha Bhama, M.D., a colorectal surgeon exclaims:

“It’s not something that we recommend that you do,” she states. “It’s not something that you need to do to maintain the health of your colon. For some people, colonic hydrotherapy can actually be dangerous.”

While concerns about the administration techniques and sanitation standards are valid, proponents of both colonics and enemas continue to argue for their health benefits. They maintain that even with modern advancements, the practice itself remains fundamentally the same—an enema still involves introducing liquid into the rectum, typically using a nozzle or catheter, much like it did in earlier times. The liquid may contain a variety of substances, including water, saline solution, or medicinal agents such as coffee or herbal infusions like chamomile for its calming effects, ginger to aid digestion, garlic for its antimicrobial properties, or aloe vera to soothe and hydrate the intestinal lining.

The Anatomy of an Enema

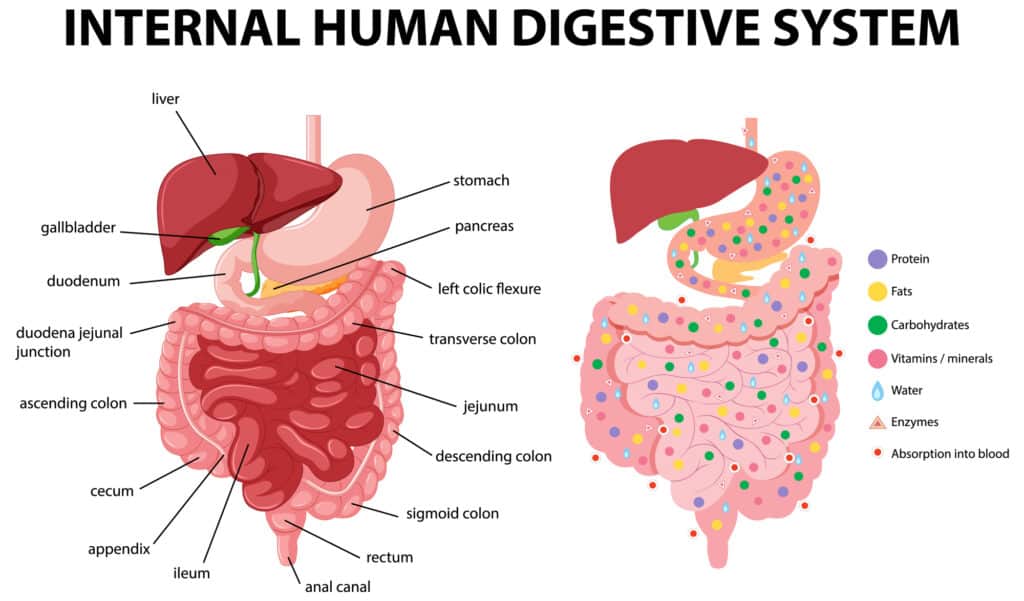

The most common purpose of an enema is to promote the evacuation of bowel contents. With modern science now able to analyze what happens inside the body, the effects of an enema can be better understood. The insertion of liquid into the rectal cavity stimulates the colon to contract, a process known as peristalsis. This movement helps to push stool through the intestines and out of your body. Enemas can also help hydrate dry, hard stool allowing it to pass. The liquid makes it softer and easier to expel. This is particularly beneficial if you are suffering from constipation due to dehydration, poor diet, certain medications (e.g., pain relievers, anti-inflammatories, or antidepressants) or medical conditions (e.g., IBS, cancer and diabetes).

There are two main types of enemas: cleansing and retention. A cleansing enema may use water, saline, Epsom salt, sodium phosphate, lemon juice, apple cider vinegar, or mild soap (such as Castile). These enemas are intended to be held in the rectum for only a few minutes to help expel hard, impacted stool. A retention enema, in contrast, is held for at least 15 minutes—and sometimes up to an hour—to allow the selected substance to take effect internally. Mineral oil, probiotics, herbs, and coffee are commonly used in this type of enema. While keeping potential concerns—such as dehydration, loss of minerals, or rectal irritation—at the forefront of considerations, many natural healthcare practitioners and wellness enthusiasts are turning to coffee enemas in conjunction with other modalities such as parasite cleanses. They are said to stimulate the colon and the liver, increasing bile production.

This enhances your body’s natural detoxification process, allowing toxins and parasites to be flushed out efficiently, helping your body to mend. While it may seem strange—and even baseless—to consider putting coffee there, historical records show that coffee enemas were used by Florence Nightingale during the Crimean War (1853–1856) to help relieve pain in wounded soldiers. Doctors later employed them for the same purpose during World War I. In the 19th century, doctors used coffee enemas to treat poisoning and postoperative shock. They remained part of conventional hospital care until the 1970s, when the shift toward evidence-based medicine (EBM) emphasized treatments that could be quantified and supported by scientific research. Coffee enemas were listed in the Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy from 1899 to 1966.

Colon hydrotherapy, or colonic irrigation, is an advanced form of colon cleansing in which large quantities of water (often around 60 liters) are introduced into the colon through a tube inserted into the rectum. The water is then flushed out, along with any accumulated waste material, gas, and toxins. Advocates of colonics claim that the process removes toxins that could otherwise lead to health issues like bloating, fatigue, and chronic disease. They argue that the colon is often “clogged” with undigested food and waste, which impairs digestion and weakens the immune system. While evidence supports the successful use of “rectal irrigation” to help with constipation and fecal impaction in patients with bowel disorders and spinal cord injuries, more studies are needed to clarify and validate this modality. Because the scientific evidence supporting the legitimacy of colonics remains limited, it has opened the door for cynicism. Dr. Michael F. Picco M.D., a gastroenterologist from the Mayo Clinic states:

“Some alternative medicine professionals believe that toxins from the digestive tract can cause headaches, arthritis and other conditions. They think that colon cleansing removes toxins and boosts energy or the immune system. But there’s no evidence that colon cleansing offers these helpful effects. What’s more, the digestive system already gets rid of waste material and germs called bacteria from the body.”

Where the Cleanse Meets the Core

While the benefits of colon cleansing remain debated, if your digestive tract is functioning properly, giving your bowels a helping hand in removing waste can help the natural systems work effectively without blocks or interference. With over 25% of North Americans suffering from chronic constipation and up to 20% from irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), it’s easy to see why you might seek solutions outside the mainstream. As the field of gut health continues to evolve, there has been a resurgence of interest in practices like enemas and colonics. Your microbiome, a vast community of bacteria and other microorganisms living in the intestines, has become a focal point of research in recent years. Studies have linked gut health to a wide range of issues, from mood and immune function to metabolism and autoimmune disorders. It’s estimated that 70–80% of your immune cells are located in the gut, influencing not only how you feel but also the functioning of other body systems. Some researchers have suggested that colon hydrotherapy could help in restoring the balance of the gut microbiota by removing harmful pathogens and promoting the growth of beneficial bacteria. However, the science in this area is still in its infancy, and much more research is needed before definitive conclusions can be drawn.

For many people, especially those in non-Western medicine communities, enemas and colonics are seen as essential parts of detoxification regimens. Proponents of detox therapy argue that modern life exposes you to an overload of chemicals, processed foods, and environmental toxins that burden the body’s natural detox pathways. Dr. Norman Walker, a well-known health advocate and naturopath, espouses the belief that regular colon cleansing through enemas or colonics is a powerful tool for preventing disease and maintaining overall health. In his book, “Colon Health: The Key to a Vibrant Life,” he points out:

“There is no ailment, sickness or disease that will not respond to treatment quicker and more effectively than it will after the administration of a series of colon irrigations.”

Similarly, Dr. Richard Schulze, an herbalist and natural medicine practitioner in Los Angeles, CA, emphasizes the importance of bowel cleansing for maintaining a strong, healthy body:

“Almost everyone’s waste removal system is slow, sluggish, even backed up and this toxic fecal waste is retained for far too long and this pollutes your body… makes you toxic, makes you sick and causes disease.”

While colonics and enemas have gained widespread popularity, safety remains an important consideration. Overuse of these methods, especially without proper medical guidance, can lead to complications, including microbial disruption. Still, their historical medical role is hard to ignore. Whether used for therapeutic or preventive purposes, bowel cleansing has endured through the ages, maintaining its appeal for those seeking natural, drug-free solutions for constipation relief, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), and other chronic gut-related diseases. Although some still view these practices with skepticism, scientific interest is growing. One study, “[Clinical and experimental study on treatment of retention enema for chronic non-specific ulcerative colitis with quick-acting kuijie powder],” noted that “retention enema with QAKJP [herbal preparation] has a good effect on CUC [chronic nonspecific ulcerative colitis], with a low recurrence rate and no toxic or side effects.” While modern medicine often prioritizes research tied to patentable drugs, home-based therapies like enemas may not draw the same investment. In the meantime, the accumulated experience—from ancient records to present-day clinical accounts—offers a valuable, if unconventional, path worth exploring.

~

Published on April 17, 2025.

If you’ve found value in this article, please share it!

To support the research and health education of AVFC editorial, please consider making a donation today. Thank you.