“Solid wastes are the discarded leftovers of our advanced consumer society. This growing mountain of garbage and trash represents not only an attitude of indifference toward valuable natural resources, but also a serious economic and public health problem.”

~ Jimmy Carter, 39th U.S. President

By Jennifer Wolff-Gillispie HWP, LC

After the first fully synthetic plastic was produced in 1907, many industries began to take a look at this invention that could replace hard to source or expensive natural materials. At the beginning of World War II, the use of plastic took off, especially in the military, as demand for lightweight and long-lasting materials became a necessity. Helmets, parachutes, tires, and components of airplanes and bombs all began to be manufactured using plastic.

The use of plastic as a replacement to other more costly, fragile, and hard to clean items skyrocketed in the post war years. In her book, “Plastics: A Toxic Love Story,” author Susan Freinkel said it perfectly:

“In product after product, market after market, plastics challenged traditional materials and won, taking the place of steel in cars, paper and glass in packaging, and wood in furniture.”

The manufacturing plants and materials that were built and developed during war time needed to be utilized and turn a profit to not be deemed a loss. Thus, the American population became inundated with public relations (PR) campaigns about all the wonderful uses of plastic. Women’s magazines such as Good Housekeeping ran stories of the many items domestic goddesses could now buy made of plastic. It was even during this time that Tupperware began to be a household name, as neighborhood wives vied for the position of top “plastic storage container queen.”

It wouldn’t be until the 1960s and ‘70s when injection molding (malleable plastic injected into a form to create a shape) and thermoforming (sheets of plastic that are heated or use vacuum or pressure to create a 3D shape) began to be used to create single use plastics. Everything from shampoo and soda bottles, condiment containers, cups and utensils, shopping bags and more, were being made with “throw away” plastic. This wasteful, disposable position was in stark contrast to why plastic was created in the first place: cheap, durable and affordable, and most of all … meant to last.

Soon after the public began to embrace the disposable plastic movement of the 1950s and ‘60s, environmentally-conscious individuals began to realize that plastic waste wasn’t just observed in heaps at the landfill, but was also seen littering oceans and landscapes. In response to this environmental threat, steps were taken on a local and national level to bring awareness to recycling.

Timeline of the Recycling Movement (Plastic, Glass and Paper Products):

- 1965–1970: The Mobius Loop (recycling symbol) designed by Gary Anderson was introduced.

- 1970: The Nation’s first Earth Day brings attention to waste and recycling.

- 1971: Oregon introduced the first “Bottle Bill” that allowed for a refundable deposit; incentivising recycling.

- 1974: University City, Missouri, became the first municipality to offer curbside recycling.

- 1976: The Federal Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) was enacted, creating standards for waste disposal at landfills.

- 1981: Woodbury, New Jersey became the first city to mandate recycling.

- 1996: The U.S. recycled at a rate between 25%–27%, and Municipal Solid Waste (MSW) decreased by nearly 2 million tons from the previous year’s statistics. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) calculated this percentage based on how many tons of MSW was collected for recycling/composting. The EPA set a new goal of 35%.

- 2000: EPA made the connection between global warming and waste, and urged that reducing refuse and recycling would cut down on greenhouse gas emissions.

- 2022: The world is producing twice as much plastic as it did two decades ago, and only 9% is successfully recycled.

Definitions: Types of Recycling

The recycling process can be broken down into two basic steps: sorting and processing. More specifically, when most plastics are recycled, they are sorted into types of plastic (“wide range of synthetic or semi-synthetic materials that use polymers as a main ingredient”), then shredded, washed, melted, and pelletized to be resold. When that is complete, they can theoretically be made into new products.

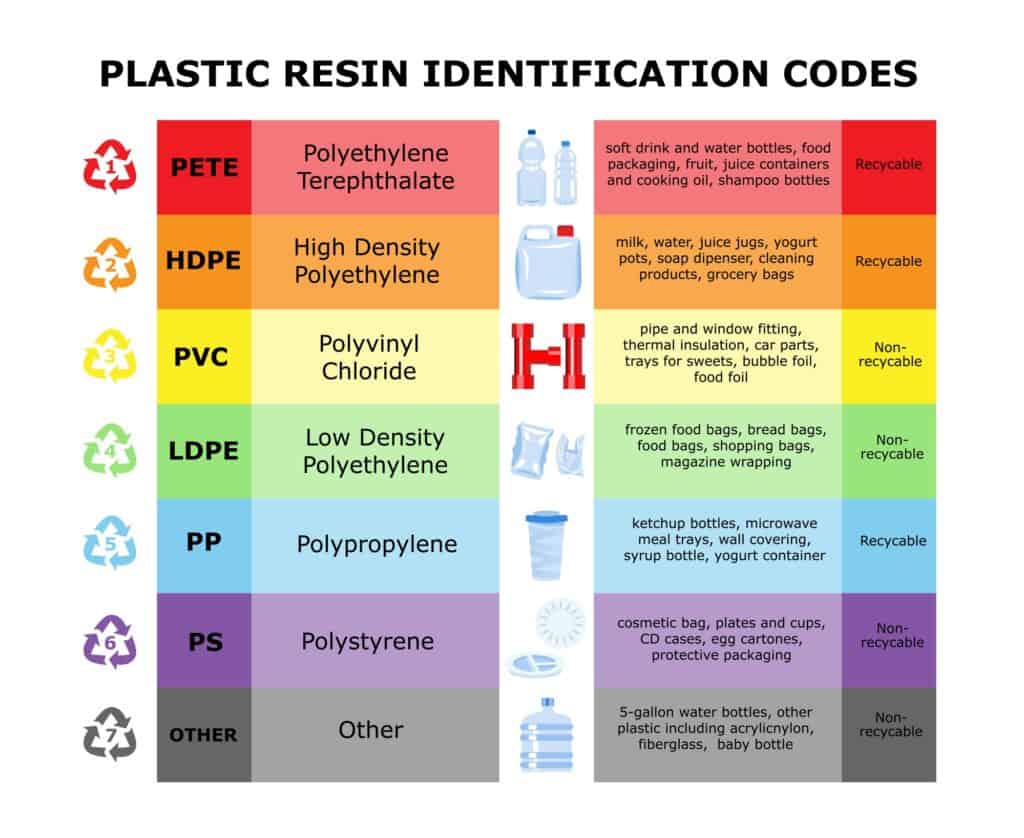

You may think the numbers on the bottom of the plastic bottles are there for you to help identify which bottles are recyclable, but that is not why they came to be. Originally, the number system was put in place by the Society of Plastics Industry (SPI) to identify the plastic resin content. Called the Resin Identification Coding System (RIC), the codes now integrate the Mobius Loop, or “Universal Symbol of Recycling” around the number. While the “chasing arrows” symbol of the Mobius Loop delineates the item as recyclable, the numbers depict unique distinctions.

Here are the specific definitions of seven types of plastics with their numbers, that you may come across:

#1 PET (Polyethylene Terephthalate): Used to make food trays and water bottles. Difficult to clean; absorbs bacteria and flavors. Avoid reusing. May be recycled into new bottles, furniture, carpet, and polar fleece.

#2: HDPE (High-Density Polyethylene): Used to make shampoo and household cleaner bottles, milk jugs, and yogurt cups. Transmits no known chemicals into food. May be recycled into detergent bottles, fencing, floor tiles, and pens.

#3: PVC (Polyvinyl Chloride): Used to make cooking oil bottles, clear food packaging, and bottles for mouthwash. Avoid. May contain phthalates that interfere with hormones and development. May be recycled into cables, mudflaps, and paneling.

#4: LDPE (Low-Density Polyethylene): Used in bread and shopping bags, carpet clothing, and furniture. Transmits no known chemicals. May be recycled into windowed envelopes, floor tiles, lumber, and trash can liners.

#5: PP (Polypropylene): Used in ketchup, medicine, syrup bottles, and drinking straws. Transmits no known chemicals into foods. May be recycled into battery cables, brooms, and rakes.

#6: PS (Polystyrene): Used to make disposable cups, plates, take out containers, and egg cartons. Avoid. Believed to leech styrene (a carcinogen) into food. Although it is possible to recycle, because of the cost and difficulty involved, it usually (at least in local municipalities) is not. There are also greater health-related concerns when recycled polystyrene comes into contact with food.

#7: Polycarbonate, BPA, and Other Plastics: Used to make three and five gallon water jugs, nylon, and other food containers. Avoid. Contains Bisphenol A (BPA) which has been linked to heart disease and obesity. Since #7 plastic is a “catch-all” category for polycarbonates, it is typically not recycled.

Most other plastics that do not have a recycling symbol and graded number, such as cling film, blister packaging, plastic-coated wrapping paper, composite plastic, bioplastics, straws, plastic bags, artificial turf, and so many others, are non-recyclable, and will end up in a landfill.

It is frightening that some components used in plastic manufacturing, once deemed safe, have been proven to be dangerous, such as BPA. This begs a few questions: Are any plastics safe to use? Are you confident that recycled plastic used for food is monitored closely enough that it is free of toxic residue? Are recycled plastics more of a concern than non-recycled plastics? While everyone will not agree on the answers to these questions, some groups unequivocally want to warn you of the dangers.

Sham Or Scam?

Greenpeace addressed plastic pollution in their full report, “Forever Toxic: The science on health threats from plastic recycling.”

From the Guardian, “Recycled plastic can be more toxic and is no fix for pollution, Greenpeace warns“:

“But … the toxicity of plastic actually increases with recycling. Plastics have no place in a circular economy and it’s clear that the only real solution to ending plastic pollution is to massively reduce plastic production.”

They go on to say that recycled plastics are actually more toxic than their newly manufactured “virgin” constituents. Additionally, Dr. Therese Karlsson, science advisor with the International Pollutants Elimination Network (IPEN), said:

“Plastics are made with toxic chemicals, and these chemicals don’t simply go away when plastics are recycled. The science clearly shows that plastic recycling is a toxic endeavor with threats to our health and the environment all along the recycling stream.”

It also highlights three “poisonous pathways,” or ways that recycled plastics can accumulate toxic chemicals:

- Direct contamination from “virgin” plastic. When plastics are made using toxic chemicals, those chemicals can transfer into the recycled plastics.

- Many studies have illustrated how plastics can absorb toxic materials through direct contact with things in the environment like pesticides, solvents, and other dangerous chemicals. These chemicals can also transfer and end up in the recycled plastic.

- New toxic chemicals can be created from the recycling process. “For example, brominated dioxins are created when plastics containing brominated flame retardants are recycled.”

In the 1990s, there was an increased public push for all citizens to join the recycling movement. Many commercials exalted the usability of plastic, yet hung the responsibility of cleaning up the environment by recycling on you, the consumer. Ironically, most of these campaigns were paid for and driven by Washington D.C. lobbyists for the plastics industry, as well as Exxon, Chevron, Dow, and DuPont (more on them later).

While the public was under the impression that it was fine to use plastic as long as you recycled, others more closely connected to the industry knew better. Laura Leebrick, manager at Rogue Disposal & Recycling in southern Oregon is one of those people. Similar to many other recycling centers, Leebrick would often send plastic trash for recycling to China (over half of U.S. plastic in 2015 went to China and Hong Kong, where it could be repurposed and sold back to Western nations. If it was dirty and unable to be cleaned, it would end up in their own landfills).

However, in 2018, when China shut the door on this business something had to give. She found a domestic buyer for milk jugs, and knew most of the other plastic garbage the public believed would be recycled, ended up buried in the landfill. ‘”To me that felt like it was a betrayal of the public trust,” she said. “I had been lying to people … unwittingly.”’

“I remember the first meeting where I actually told a city council that it was costing more to recycle than it was to dispose of the same material as garbage,” she says, “and it was like heresy had been spoken in the room: You’re lying. This is gold. We take the time to clean it, take the labels off, separate it and put it here. It’s gold. This is valuable.”

Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) FRONTLINE and National Public Radio (NPR) spent months digging into this issue, and found through internal industry documents and interviews of former officials, that as the nation’s largest gas and oil companies were spending millions of dollars convincing the American public of the benefits and ease of recycling they knew full well wouldn’t work, but kept on as they sold billions in new plastic.

“If the public thinks that recycling is working, then they are not going to be as concerned about the environment,” Larry Thomas, former president of the Society of the Plastics Industry, known today as the Plastics Industry Association, and one of the industry’s most powerful trade groups in Washington, D.C., told NPR.

So who is behind the making and manufacturing of all this plastic? Exxon Mobil Corporation (the world’s leading plastic manufacturing company), worth $458.7 billion dollars, followed by LG Chem, Ltd. (LG Chemical) at $204.5 billion, Dow, DuPont, BASF, Koch Industries, Chevron, and many more, that’s who. The same people pushing for more policy in regards to recycling are the ones covering up the failures in existing programs; all the while continuing to profit in the market of new plastics.

Even with robust recycling programs, California’s CalRecycle reports that 12,000 tons of plastic ends up in landfills daily! That’s 4,380,000 tons per year, and 10% of all the waste that ends up in the landfill. In 2022, California Governor, Gavin Newsom, signed SB 54 requiring 100% of packaging in the state be recyclable or compostable, 25% of plastic packaging be cut, and 65% of all single-use plastic packaging be recycled by 2032.

As stated in the bill:

“The act requires disposal facility operators to submit information to the department on the disposal tonnages that are disposed of at the disposal facility, and requires solid waste handlers and transfer station operators to provide information to disposal facility operators for purposes of that requirement. The act requires recycling and composting operations and facilities to submit periodic information to the department on the types and quantities of materials that are disposed of, sold, or transferred to other recycling or composting facilities or specified entities.”

Regardless of changes in policy on the horizon, the need to reduce dependency on plastics should be of concern. The continued question of personal health and safety, as well as environmental risks are increasingly hard to ignore. Take a moment to notice all the ways plastics have become a part of your everyday life, and see where and how you are willing to make adjustments. Here are some simple ways to start:

- Buy grains, beans, spices and more in bulk, and refill your glass storage containers; mason jars work great for this. If you can not bring your reusable containers to the store, reuse the store’s bags for transport.

- Shop at farmer’s markets, and bring your own canvas bags. Do not buy produce in plastic packaging.

- Use bar soap instead of liquid soap for cleaning and personal care. A safe, natural multi-purpose soap such as Dr. Bronner’s works great.

- Buy food items like tomato sauce, condiments, and drinks in glass instead of plastic. You can source food in cans, but glass containers can be washed and reused for other purposes.

- Replace ziplock bags and plastic storage containers with reusable beeswax wraps and glass storage containers.

- Choose metal or wood toys for your children instead of plastic.

- Use real silverware, plates, and cups instead of plastic, and forgo the use of plastic straws at restaurants and cafes. You can also invest in reusable metal or silicone straws.

- Bake or make your own bread, soups, dressings, yogurt, and many other items, ditching the plastic wrapping and plastic cups they come in at the grocery store. You can store homemade food in mason jars, and wrap bread in a tea towel or butcher’s paper.

- Compost as much food waste as you can to cut down on the amount of trash you produce, and therefore the amount of plastic trash bags you use. In addition, you can purchase biodegradable trash bags.

It is without a doubt that plastic use is here to stay, but the collective over-dependency absolutely needs to be considered and addressed. There have been recent scientific discoveries of bacteria/microbes that can digest plastic, but until these technologies are further developed and implemented, taking a hard look at your plastic consumption is in order. If you are aware of how and why the problem exists, and are mindful of your choices moving forward, you can contribute to real, positive change—not just for yourself, but for the whole planet.

~

Published on November 23, 2023.

To contact A Voice For Choice Advocacy, please email media@avoiceforchoice.org.

If you would like to support the research and health education of AVFC editorial, please consider making a donation today. Thank you.